- Title: Atomic Habits

- Author: James Clear

- Year Published: 2018

Introduction

changes that seem small and unimportant at first will compound into remarkable results if you’re willing to stick with them for years. We all deal with setbacks but in the long run, the quality of our lives often depends on the quality of our habits.

The Fundamentals

1. The Surprising Power of Atomic Habits

-

Uses the example of how Brailsford’s team transformed the success of British Cycling by making small 1% improvements in overlooked areas of their cycling training to improve the performance of the team

-

We overestimate defining moments and underestimate small, daily improvements to our lives, thinking that big success needs big action

-

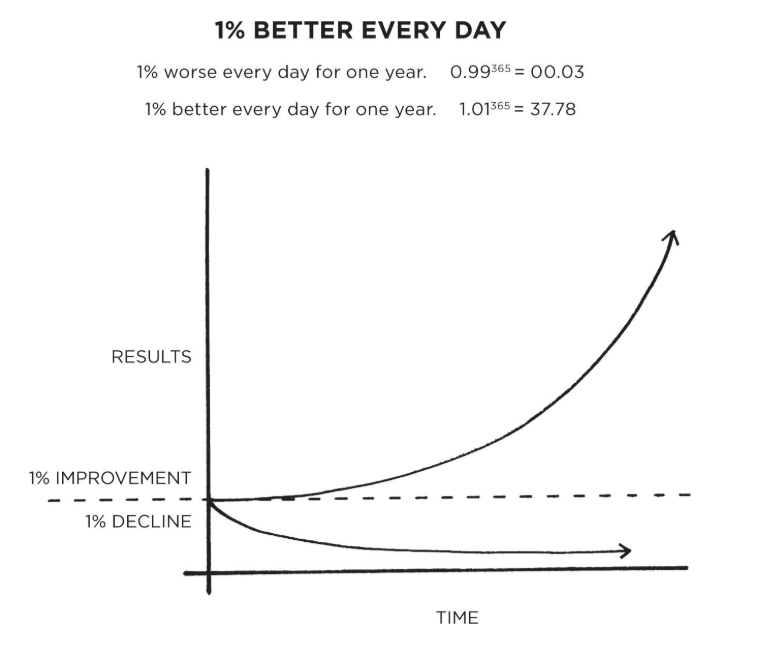

Meanwhile, improving by 1% through small habits is more meaningful in the long-term, even if their effects are not noticeable in the short-term, because small habits compound over time: if you get 1% better every day, after a year you will be 37 times better

Habits are the compound interest of self-improvement

-

Making a 1% better or 1% worse choice in a given moment seems insignificant, but in the long-term these choices add up

-

Success then is the product of daily habits realising your potential of who you can be, gradually adjusting the trajectory of your life, as the results of habits are magnified and compound with time

- To estimate the result of starting a habit, follow the curve of 1% gains or losses to see how they compound over the long-term

Good habits make time your ally. Bad habits make time your enemy.

- This makes habits a “double-edge sword”

- You need to know how habits work and scale in the long-term to design them to favour the beneficial over the dangerous edge of the habit blade

-

This means that you should concentrate on your current trajectory rather than your current results, because the outcomes of a habit lag behind the implementation of the habit: “You get what you repeat”

-

-

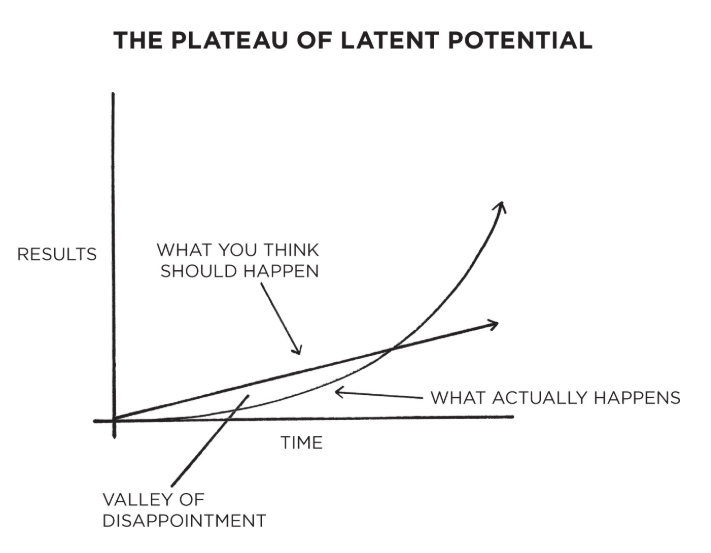

This compounding effect means that habits seem to not make any difference until a critical threshold is breached and a result becomes apparent

Breakthrough moments are often the result of many previous actions, which build up the potential required to unleash a major change.

- We expect our progress from a habit or change to be a linear process, but in reality (because of the compounding effects of habit) results are often delayed

- The Valley of Disappointment is where you do not feel you are making any progress, because the real pattern of change does not align with your expected pattern of change and results from introducing a habit

- To make a difference, habits have to be maintained through the Plateau of Latent Potential (where tangible results are not apparent from making a change or dealing with a habit), after which a ‘breakthrough success’ seems apparent (which itself obscures the long-term work done through habits into achieving success!)

All big things come from small beginnings.

-

Goals help us set a direction for change, but systems are better for actually making the progress to achieve these goals

- Goals: the results you want to achieve

- Systems: the processes that lead to the results / goals you want to achieve

Forget about goals, focus on systems instead

- This is because the only way to make change is to make small improvements every day

- 4 problems with thinking too much about goals and not spending enough time coming up with good systems to achieve them

-

“Winners and losers have the same goals” ⇒ the goal doesn’t differentiate winners from losers

-

Achieving a goal is only momentary, as problems solved at the results level are temporary, and problems solved at the systems level are long-term ⇒ “Fix the inputs and the outputs will fix themselves

(e.g. solving a messy room as a symptom / goal is temporary, unless you redesign the systems that are producing the mess in the first place!)

-

Goal-first mentalities encourage you to put happiness to the side until you achieve your goal, creating a single scenario of success in which you can be happy. System-first mentalities mean that the process of achieving results make you happy, rather than the result.

-

Goal-oriented mindsets do not mesh well with ideas of long-term progress: setting goals is about winning the game (finite) and building systems is about playing the game (infinite) ⇒ “long-term thinking is goal-less thinking”, “about the cycle of endless refinement and continuous improvement”

Ultimately, it is your commitment to the process that will determine your progress

-

You do not rise to the level of your goals. You fall to the level of your systems

- Habits are like atoms, they are units that build together to contribute to a net improvement and to the achievement of results

- Atomic habits: regular routines that are small and easy to do, but are powerful through creating systems of compound growth

2. How your habits shape your identity (and Vice Versa)

-

Changing habits is challenging because (1) we don’t change the right thing, and (2) we don’t change our habits in the best way

-

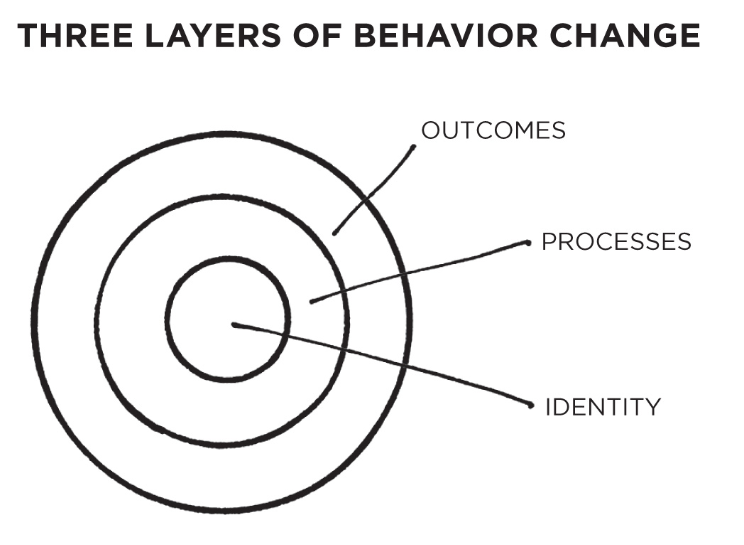

There are 3 levels of behaviour change:

- Outcomes: results (e.g. publishing a book), the level of change where most goals are set

- Processes: the systems that you follow and the practices you do to achieve certain outcomes

- Identity: what you believe

- All of these levels of change are important, but the direction in which we make these changes is perhaps not always the best one

- Most people build outcome-based habits, based on what they achieve, rather than identity-based habits, based on who we want to be

Behind every system of actions are a system of beliefs

- Habits last when the behaviours involved align with our belief systems

The ultimate form of intrinsic motivation is when a habit becomes part of your identity. It’s one thing to say I’m the type of person who wants this. It’s something very different to say I’m the type of person who is this.

-

If you are proud of your identity and what you believe, you will be more motivated to maintain the habits and systems of actions that are associated with this belief system

There is internal pressure to maintain your self-image and behave in a way that is consistent with your beliefs. You find whatever way you can to avoid contradicting yourself

⇒ behaviour change is identity change; and identity change invokes behaviour change

- Improvements persist when the actions that sustain them become a part of who you are and your identity

- So, to be the best version of yourself, you have to constantly edit and change your belief system to upgrade and progress your identity

habits are how you embody your identity

Every action you take is a vote for the type of person who you wish to become

- Because identity change and habit change depend on eachother, to change your identity (and hence habits) you:

-

Decide who you want to be

- e.g. work backward from results to the type of person who gets these results

What is the type of person who could/would _____?

-

Prove that you are this type of person through small wins

-

Identity change is the North Star of habit change

- Habits matter because they can help you change your beliefs about yourself, rather than because they can get you results (although this is often a side-effect!)

3. Hot to Build Better Habits in 4 Simple Steps

-

Habits are automatic solutions to solve regularly encountered problems

- They are cognative scripts and shortcuts learnt through experiences

- They free up mental capacity so we can focus on other tasks

- ood habits make life easier so you have the space for free thinking and creativity

Building habits in the prsent allows you to do more of what you want in the future.

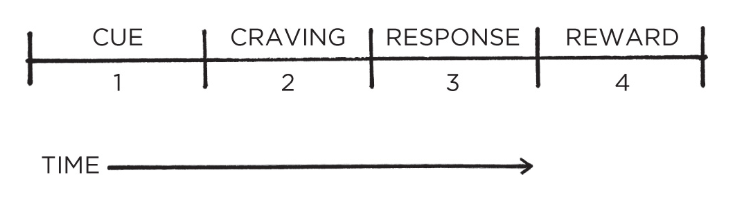

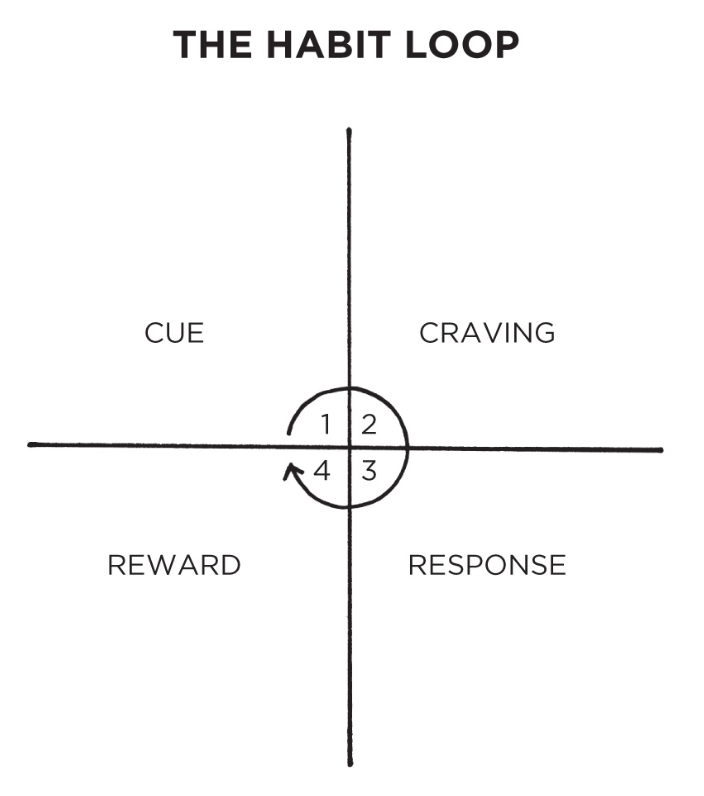

- Building a habit involves 4 steps

-

Cue: an indication of a possible reward, triggering the start of a behaviour [notice reward]

-

Craving: the motivation to change an internal state (differ between people), triggered by a certain cue [want reward]

-

Response: the actual habit performed (thought or action), depending on the friction to a behaviour and your ability to do it [obtaining reward]

-

Reward: the end goal of habits, because they satisfy our cravings and teach us what actions to learn and remember

Your brain is a reward detector.

- The reward is a part of a feedback mechanism that encourages you to repeat certain actions again

- Without a cue, craving and response a certain behaviour won’t happen; and without a reward, you won’t do the behaviour again

- The Habit Loop: cue triggers a craving, motivating a response, providing a reward, satiating the craving, and becoming associated with the cue

- The habit loop is endless, as the brain constantly looks for cues and learns from the results of different responses to those cues

-

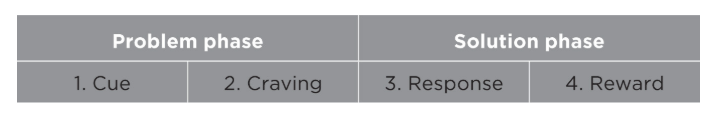

We realise something needs to change / happen in the problem phase, and we take action to achieve this change in the solution phase

- Habits have a purpose to solve problems that we face

-

- The Four Laws of Behaviour Change: a framework to create good habits and break bad habits

- When these laws are in the right positions, it is easy to create good habits and break bad ones

- Creating good habits

- Cue: make it obvious

- Craving: make it attractive

- Response: make it easy

- Reward: make it satisfying

- Breaking bad habits

- Cue: make it invisible

- Craving: make it unattractive

- Response: make it difficult

- Reward: make it unsatisfying

- These laws are close to a universal strategy to change habits

- To change your behaviour, ask yourself:

- How can I make it obvious, attractive, easy and satisfying?

- The key to good habits is understanding these fundamental laws of behaviour change, and hence human nature in terms of how we interact with and think about habits

The 1st Law: Make it Obvious

4. The man who didn’t look right

The human brain is a prediction machine. It is continuously taking in your surroundings and analyzing the information it comes across

- The process of building habits, learning lessons of how to solve problems through experience, is automatic, as your brain catelogues cues and behaviours that lead to desirable results

- The fact that our brain notices cues and takes action automatically (without fthinking) is what makes habits so useful and dangerous

- So, to build better habits, we have to be aware of our current ones — if a habit is mindless you can’t improve it

-

e.g. Japanese Pointing-and-Calling system to reduce mistakes, reducing errors by 85% because it raises train operators' awareness of habits

-

The Habits Scorecard is an exercise you can do to become more aware of your habits

-

Make a list of daily habits

-

Ask whether each habit is a good (+), bad (-) or neutral (=) habit

There are no good habits or bad habits. There are only effective habits. That is, effective at solving problems

- But, in the long term:

Habits that reinforce your desired identity are usually good. Habits that conflict with your desired identity are usually bad.

-

-

5. The best way to start a new habit

-

Implementation intention: a plan you make about how you intend to implement a particular habit

-

Hinges on the most common habit cues of time and location, by making them obvious

**I will do X at TIME in LOCATION**e.g. I will mediate for one minute at 7 a.m. in my kitchen

-

Scientifically proven to help us stick to our goals and intentions

people who make a specific plan for when are where they will perform a new habit are more likely to follow through.

- Helps us figure out the basic details of how we can implement a new habit, rather than leaving it up to chance burst of motivation ⇒ gives clarity to our habit formation process

When your dreams are vague, it’s easy to rationalize little exceptions all day long and never get around to the specific things you need to do to succeed.

-

applying implementation intentions (where new habits are paired with current habits rather than a certain time and space)

-

Habit stacking: stacking new habits ontop of existing habits you already do every day

- An extension of the Diderot Effect (where buying a good creates a spiral of consumption that drives additional purchases), by deciding what you do next based on what you just did ⇒ every action becomes a cue that triggers other actions

**After CURRENT HABIT, I** will **do NEW HABIT**e.g. after I pour my cup of coffee in the morning, I will meditate for one minute

- About tying a desired behaviour into things you already do everyday

- You can build bigger stacks by chaining several small habits together, using the result of each habit as a cue for the next one, mobilising the momentum of the Diderot Effect

pour morning cup of coffee → meditate for 60 seconds → write to-do list → begin first task

-

You can also add new behaviours into the middle of routines (e.g. wake up → make bed → place book on pillow → take a shower)

Make sure that the part of your daily routine that you are inserting the habit into is appropriate

- Criteria for a routine to be appropriate for habit stacking

- Has the same frequency of desired habit

- When the habit is most likely to be successful

- You can identify triggers for potential habit stacks by brainstorming current habits (e.g. Habits Scorecard), perhaps by writing down all the habits you do every day, and then another list of all the things that happen to you every day (to identify the best place to layer in your new habit)

- Criteria for a routine to be appropriate for habit stacking

habit stacking allows you to create a set of simple rules that guide your future behaviour. It’s like you always have a game plan for which action should come next.

-

You can then work to build general habit stacks that are situation-dependent

- e.g. social skills: when I walk into a party, I will introduce myself to someone new

-

The key to making a successful habit is selecting the best cue to initiate the new habit

- Works best when the cue is very specific and immediately actionable

Key mistake: having vague cues

e.g. when I close my laptop for lunch, I will do ten push-ups next to my desk

- About providing clear instruction about how and when to act

- This is about making your cue obvious so you are more likely to act on it and build your habit

6. Motivation is overrated: environment often matters more

Environment is the invisible hand that shapes human behaviour.

- Lewin’s Equation: Behaviour is a function of the person in their environment

- The actions we take reflect the more obvious option in our environment

You don’t have to be the victim of your environment. You can also be the architect of it.

- We can draw our attention towards a desired habit by creating obvious visual cues in our environment (e.g. making water bottles visible about your home; putting a book on your pillow)

If you want to make a habit a big part of your life, make the cue a big part of your environment

-

This environmental design is powerful because it influences how we engage with the world, and because we often don’t do it!

Be the designer of your world and not merely the consumer of it

-

Context can also act as a cue, as the situation that reproduces certain behaviours

- This is because our behaviours are influenced by how we relate to our environment (the context) rather than certain objects in the environment (e.g. a sofa as a reading place or to browse social media)

- It is important to link habits with distinct, specific contexts (e.g. office for work; living room for relaxation; laptop for reading; phone for social media)

- It is easier to change habits by changing to a new environment, to escape the familiar objects that we already have relationships to that nudge us towards certain behaviours

- If you can’t create a new environment, you can change habits by redefining your relationship to, or rearranging, your current one by creating distinct spaces for different uses

- If you mix contexts, you mix habits (and the easier ones usually win, such as watching tv) because multiple cues are competing for your attention simultaneously

- Associate contexts with a certain frame of mind, as habits work best in stable environments

7. The secret to self-control

- Self-control is only a short-term strategy: as ‘discipline’ in the long-term is not about heroic willpower, but instead about living in a way that avoids tempting situations

- It is easier to have self-control if you don’t need to have it often!

- You get greater self-control by creating a disciplined environment

- Once you notice a cue that drives a bad habit, you begin to crave the bad habit

- Once you form a habit, you are unlikely to forget it

- So, one of the best ways to eliminate and break bad habits is reducing your exposure to cues causing them

- The secret to self-control is about making the cues driving good habits obvious, and the cues of your bad habits invisible

The 2nd Law: Make it Attractive

8. How to make a habit irresistible

-

Supernormal stimuli: heightened versions of reality that are powerful cues that trigger very strong responses (humans are coded to fall for these types of stimuli)

We have the brains of our ancestors but temptations they never had to face

- To make it more likely for a certain behaviour to occur, you have to make it attractive

- 2nd Law of Behaviour Change: Make it attractive

- If a behaviour is attractive, it is more likely to be habit-forming

- To make it more likely for a certain behaviour to occur, you have to make it attractive

-

Habits are dopamine feedback loops, where habit forming activities are linked with heightened level of dopamine in the brain

- Dopamine is released when we anticipate a reward (and is only released when we experience pleasure when we do not expect it)

- This means that the anticipation, rather than the fulfilment, of a reward drives action

- Our brains have greater neural capacity allocated for wanting than liking rewards

Desire is the engine that drives behaviour

-

Temptation bundling is where you link actions you want to do with actions you need to do

- This hinges on the idea that you are more likely to find certain behaviours attractive if you can do one of your favourite things

- Application of Premack’s Principle: “more probable behaviours will reinforce less probable behaviours”

Combining habit stacking with temptation bundling:

1. After [**CURRENT** HABIT], I will do [HABIT I **NEED**] *Habit stacking* 2. After [HABBIT I **NEED**], I will do [HABIT I **WANT**] *Temptatino bundling*e.g. Want to read the news, but need to express more gratitude

- After I get my morning coffee (current), I will say one thing I’m grateful for that happened yesterday (need)

- After I say one thing I’m grateful for, I will read the news (want)

- Eventually, you will look forwards to doing the habit you need to do, because you get to do the thing that you want to do

- This is about creating heightened versions of habits to make them more attractive

9. The role of family and friends in shaping your habits

- Culture and social norms influence what behaviours seem attractive (because they allow us to fit in)

- This is because humans are herd animals, wanting to fit in and gain social approval

- The result is that we imitate habits from society to meet cultural expectations and fit in

- We imitate the habits of 3 social groups

-

The close: family and friends

- The closer you are to a person, you are more likely to imitate their habits

Peer pressure is bad only if you’re surrounded by bad influences

- New habits are achievable if others do them every day

- So, join a culture (e.g. club) where:

- the behaviour you desire is normal (⇒ idea that your desired habit is a common habit)

- you have something in common with the group (⇒ idea of ‘people like me do something’)

- Belonging to a tribe of like-minded individuals transforms your personal quest into a shared quest, keeping you motivated to maintain a habit ⇒ a shared identity reinforces your personal identity

-

The many: the tribe

- The normal behaviour of the tribe can overpower an individual’s desired behaviour, because of the internal pressure to comply with group norms ⇒ there is an overpowering reward of acceptance

- Our natural mode is to get along with others ⇒ it takes work to go against the cultural grain

- Change is more attractive if changing your habits involves fitting in with a tribe rather than challenging the tribe’s norms

-

The powerful: those with status & privilege

- Habits are more attractive if they gain us approval, praise and respect (as a person with greater power historically has greater means of survival), and less attractive if they lower our social standing

- Driven by a continual question of what will others think of me? (altering our behaviour based on this)

- When we fit in, we want to stand out and dominate the crowd

- This drives people’s interest in the habits of effective people, as we copy the behaviour of people whose success we envy and admire

- Habits are more attractive if they gain us approval, praise and respect (as a person with greater power historically has greater means of survival), and less attractive if they lower our social standing

-

10. How to find and fix the causes of your bad habits

-

Cravings and habits are motivated by deeper underlying motives (e.g. to conserve energy, obtain food and water, gain social approval, reduce uncertainty)

- Habits try and address the motives of human nature ⇒ “modern-day solutions to ancient desires”

- There are many ways to address an underlying motive, and your current habits may not be the best way to solve them!

- But, if a habit is successful in addressing a motive, we crave to perform this action again to solve the problem next time

- Our behaviour depends on how we interpret events, rather than the reality of events, because this shapes what we predict will happen, and hence how we react to this prediction

- Cravings are produced (and hence habits caused) by predictions

- Cravings are about wanting to feel differently than we do right now, and the difference between how we feel now and want to feel creates a desire to act

- Habits are attractive if we associate them with a result of good feelings

-

So, hard habits are more attractive if you associate them with positive experiences (through a mind-set shift)

-

We can see certain behaviours as not burdens that we have to do, but opportunities that we get to do

You don’t “have” to. You “get” to.

Reframing your habits to highlight their benefits rather than their drawbacks is a fast and lightweight way to reprogram your mind and make a habit seem more attractive

e.g. “I need to go run in the morning” → “it’s time to build endurance and get fast”

e.g. distractions when you meditate are irritating → distraction is good as it allows us to practice returning back to the breath and get better at meditating

e.g. pregame jitters “I am nervous” → “I am excited and I’m getting an adrenaline rush to help me concentrate”

-

These mind-set shifts change the feeling we associate with certain habits and situations

-

Motivation rituals: where you associate cues with resulting in something you enjoy, to create a cue and craving for a certain mindset or to perform a desired difficult habit

e.g. create a routine (e.g. take 3 deep breaths and smile) before you do something you love (e.g. petting a dog), so that the routine becomes associated with being in a good mood. Then, every time you want to change your mind-set to become happier throughout the day, you can use this routine as a cue to create a craving for a happier emotional state

-

-

Likewise, you can make bad habits unattractive if you highlight the benefits of not doing them and associate them with negative experiences and consequences

The 3rd Law: Make it Easy

11. Walk slowly, but never backward

-

It is easy to become obsessed with trying to find an optimal plan for change, so that we never get round to actually executing it

- Being in motion: planning, strategizing, learning (e.g. planning the perfect diet)

- Being in action: behaviour that delivers outcomes and results (e.g. eating healthy meals)

Motion makes you feel like you’re getting things done. But really, you' re just preparing to get something done.

- You need to act if preparing to act becomes a form of procrastination

If you want to master a habit, they key is to start with repetition, not perfection. You don’t need to map out every feature of a new habit. You just need to practice it.

-

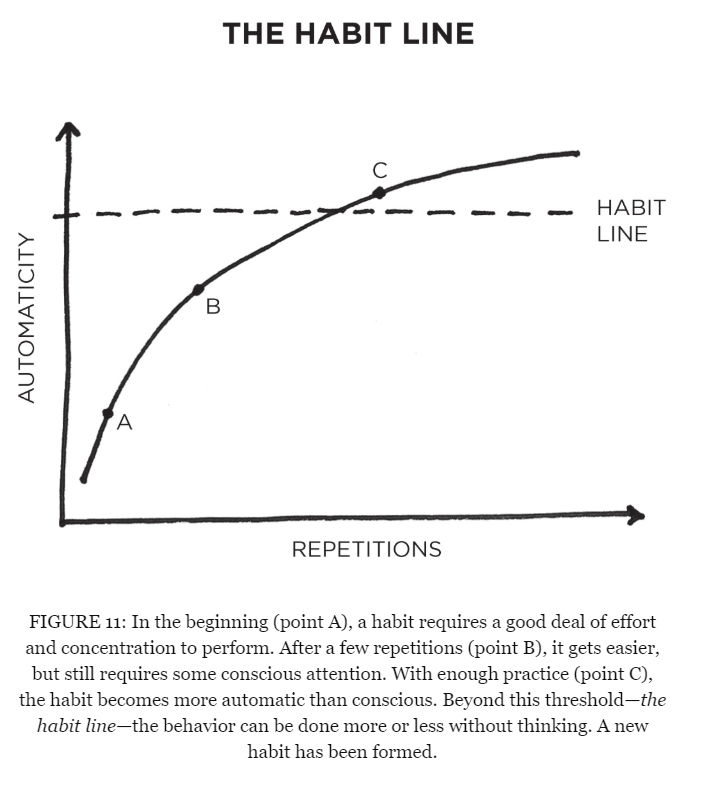

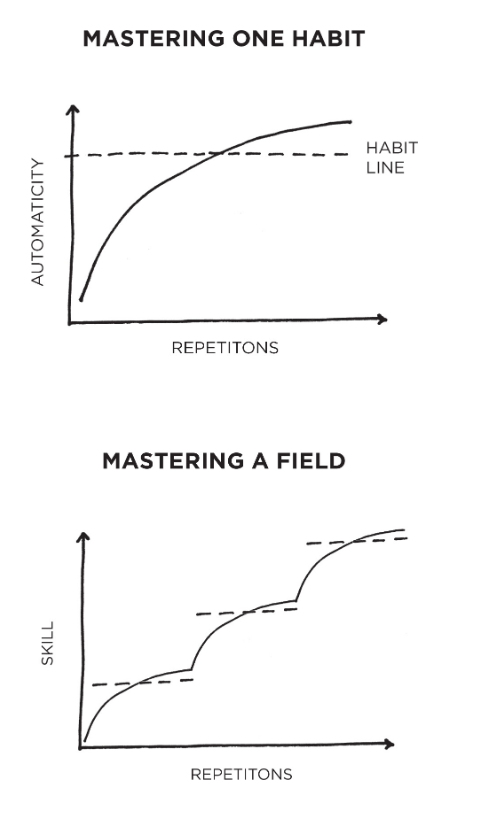

Habit formation: the process where a behaviour, through repetition, becomes increasingly automatic

- This is because the more times a behaviour is repeated, the stronger cell-to-cell signalling and neural collections for the assossiated patterns of brain activity become (long-term potentiation or Hebb’s Law: “Neurons that fire together wire together”)

Like the muscles of the body responding to regular weight training, particular regions of the brain adapt as they are used and atrophy as they are abandoned

-

Because each time you do something, a mental neural circuit related to that habit is activated, repetition is one of the most important steps to building new habits

-

Automaticity: the process where a habit moves from becoming an effortful to automatic behaviour, where we can before behaviours without thinking about each step

-

The habit line is an example of a learning curve

habits form based on frequency, not time

- The question isn’t about how long it takes to build habits, but about how many repetitions it takes to make a habit automatic

- So, crucial to building habits is practicing the desired behaviour successfully enough time to cross the ‘Habit Line’ (where the behaviour is automatic / non-conscious)

-

This means that to build a habit, you have to practice it. And you are more likely to practice it if you make it easy to practice

12. The law of least effort

-

Traditionally, the idea is that motivation is central to habit change: that if we wanted something we would do it. But really, out motivation is to be lazy and take the most convenient option

- The brain is wired to conseve energy, such that human behaviours follow the path of least effort or resistance

- We choose actions that give us the most value for giving the least amount of effort

We are motivated to do what is easy.

- So, if a habit takes less energy and it convenient to do, we are more likely to do it

-

We don’t want to do habits, but we want the outcome from doing them

- The more difficult a habit is, the more friction there is to get the outcome

- It is crucial to make habits easy so you do them even if you don’t ‘feel like it’

The idea behind make it easy is not to only do easy things. The idea is to make it as easy as possible in the moment to do things that pay-off in the long run.

-

Focus on reducing rather than overcoming friction in your life [REMOVING POINTS OF FRICTION]

- Environmental design is a great way to make desirable behaviours easier

- Habits are more likely to develop if they fit into your life and your routine

- e.g. choose a place to practice a habit that is along the path you take in your daily routine (e.g. on the way to work) rather than out of your way

e.g. “lean production” of Japanese Firms in the 1970s to remove waste and points of friction in the production progress to increase efficiency and productivity: addition by subtraction

when we remove the points of friction that sap our time and energy, we can achieve more with less effort

- Good habits form better when the friction to carrying them out is removed, and bad habits are more easily broken when the friction to doing them is increased

-

Priming the environment for future use: once you have finished in a space, organise it for its intended purpose, to make carrying out the habit in that space easy (by reducing the friction to doing it)

-

About making the good habit the path of least resistance in every moment

e.g. to draw more: put pencils, pens, notebooks and drawing tools on top of your desk in easy reach, making them a no-brainer in a break

e.g. to exercise more: set out / pack workout gear ahead of time

-

Likewise, you can prime the environment to make bad habits really inconvenient (e.g. unplugging the tv after each use, and only plugging it back in if you have a clear intention of what you are going to use it for)

e.g. to work without interuption: leave your phone in a different room so you don’t think about it and it is inconvenient to use

- It is suprising how unwanted behaviour doesn’t happen with even a very small amount of friction

-

The effect of priming the environment is cumulative, designing a lifestyle where we prioritise good behaviours over bad ones

-

Redesign your life so the actions that matter most are also the actions that are easiest to do.

13. How to stop procrastinating by using the two-minute rule

Habits are like the entrance ramp to a highway. They lead you down a path and, before you know it, you’re speeding toward the next behaviour

-

It is easier to continue with a task than start something completely different

- So, we can use habits to get us started with tasks, and hence shape what we do

-

Decisive moments: moments int eh day that give an outside impact for waht you do in them: they “set the options available to your future self”

-

These are key habitual choices that shape the trajectory for how you spend moments in your day

-

Think of them like forks in the road of your everyday life

e.g. start homework vs grab video game controller

-

Your options afterwards are constrained by the initial choice (e.g. the type of restaurant you go to modifies the dishes you can order)

-

Their effect of decisions in these decisive moments is cumulative, determining the outcome of the day

Habits are the entry point, not the end point. They are the cab, not the gym.

-

-

Two-minute rule: when you start new habits, they should take less than 2 minutes to do

Use when you are struggling to stick with a habit, as a simple way to make them easy

- To counteract our tendency to start too big when we get excited about changing how we do things

e.g. read before bed each night → read one page before bed each night

- About making habits super easy to start ⇒ “gateway habits” guiding you onto a desired path or way of living

- This is powerful because when you begin doing the right thing (vs. procrastinating doing it), it is easier to continue doing the right thing

- When you ritualise the start of a habit, you are more likely to continue with the behaviour once you get into it

How do you figure out gateway habits to gradually get your desired outcome?

Map out goals from very easy to very hard

e.g. goal: run a marathon; gateway habit: put on running shoes

e.g. goal: write a book; gateway habit: write one sentence

-

Starting small is not pointless, as just showing up is a small confirmation of who you want to be

The point is to master the habit of showing up

(vs spending ages trying to engineer the ‘perfect’ habit before you’ve tried it!)

-

Once you are doing an easy, ‘gateway habit’ consistently (standardising), you can then optimise it ⇒ “You can’t improve a habit that doesn’t exist”

- Habit shaping: gradually building up a habit over time to get closer to the full habit that you want to have, while maintaining a focus on making the first 2 minutes of the behaviour as achievable and easy to do as possible

It’s better to do less than you hoped than to do nothing at all

-

When doing a habit stop just below the point where doing the habit feels like a chore or work (to maintain the idea that it is easy to do (vs a chore))

14. How to make good habits inevitable and bad habits impossible

- Success also involves making bad habits hard to make it easier to stay on track

- Commitment device: where you make a choice in the present that controls the selection of actions you can take in the future (to bind you to good habits)

-

They enable you to use your good intentions before you get tempted

-

You change a task so that it is harder to get out of the good habit (when it is easy to start)

e.g. set up a yoga class and pay ahead of time (the only way to bail on your good habit is the effortful and expensive cost of cancelling the class)

-

automating your habits to lock in good future behaviour

-

Making a bad habit impractical or impossible can be an effective way to break it ⇒ increasing the friction to the point where the bad habit isn’t even an option you can take

-

This is often driven by one-time actions that take a little bit of effort to get in place, but result in value over time by stopping bad habits and locking in good ones

e.g. productivity: unsubscribe from emails; turn off notifications; set phone to silent on a schedule; delete games and social media apps from your phone

e.g. sleep: buy a good mattress; get blackout curtains; remove tv / phone from bedroom

-

Removing the “mental candy” from your environment to make it “easier to eat the healthy stuff”

-

-

Technology can make hard, complicated actions easier

e.g. website blockers to stop social media browsing

-

Can be useful through automating good behaviour so technology remembers to do the habit for you (e.g. automatic wage deduction for pension) if it is not repeated often enough for it to become a strong habit ⇒ handing over habits to technology to free up our time to pursue habits machines can’t do for us

When you automate as much of your life as possible, you can spend your effort on the tasks machines cannot do yet.

-

Can work against us too (e.g. binge-watching features make it easy to continue watching TV)

Technology creates a level of convenience that enables you to act on your smallest whims and desires.

- It is easy to act on our desires, but this only encourages us to jump between easy tasks rather than make time for difficult, rewarding work (e.g. the tug of ‘one more minute’)

-

The 4th Law: Make it Satisfying

We are more likely to repeat a behaviour when the experience is satisfying.

- The first 3 laws of behaviour change (make it obvious, attractive and easy) make it more likely that a behaviour will happen this time, while the fourth law (make it satisfying) makes it more likely that it will happen again (completing the habit loop)

15. The cardinal rule of behaviour change

Compared to the age of the brain, modern society is brand-new

-

The human brain evolved in an immediate-return environment, but we live in a mainly delayed-return environment

resulting in…

-

Time inconsistency: where we value the present more than the future (so prioritise certain, short-term rewards over possible, long-term rewards)

- Bad habits: immediate outcome usually feels good, but the eventual outcome bad

- Good habits: immediate outcome usually is unenjoybale, but the ultimate outcome enjoyable

- Good habits have a short-term cost, while bad habits have a long-term cost

- Because the brain prioritises the prseent moment, despite our good intentions when we have to make a decision, instant gratification often wins

-

Cardinal rule of behaviour change: “What is immediately rewarded is repeated. What is immediately punished is avoided”

-

So, to make a habit stick you have to make it feel instantly successful (even if only in a small way), making the brain feel like the behaviour was worth it

-

The ending of the habit has to be satisfying (because we remember it more)

-

Reinforcement: tying your habit to an immediate reward to make it satisfying to finish

- Select short-term rewards that reinforce your desired identity (e.g. reward for exercising is a massage, which is enjoyable, and a vote towards your desire to have an identity where you take care of your body)

- This can also be useful for habits of avoidance (e.g. every time you pass on a purchase, you put the money you would have spent into a savings pot ⇒ “a loyalty program for yourself”

-

Immediate rewards are essential in the beginning of habit building, to give you a reason to stay on track and be excited while the delayed rewards (which are why you do the habit in the first place) accumulate

- As eventually the intrinsic rewards that result from a habit (e.g. better mood or less stress) make you less concerned about the secondary, short-term reward, as you begin to do the habit because it is a part of who you are

Incentives can start a habit. Identity sustains a habit.

-

16. How to stick with good habits every day

-

Progress is satisfying, and we can use visual measures to give evidence of progress

-

Habit trackers are a great way to visually measure progress

- Measuring whether you did a habit on a given day

- As time goes by, the habit tracker becomes a visual record of your ‘habit streak’

- Hinges on the idea of “don’t break the chain": not about how well you perform, but about showing up

- Makes a behaviour obvious: by building a series of visual cues that remind you to act (where each time you do a habit or see your streak you are reminded to act again)

- Makes a behaviour attractive: habit tracking is motivating and addictive as you don’t want to lose the progress you are making (a series of small wins)

- It also motivates you to do a habit on a bad day by acting as a gentle reminder of how far you’ve come in practicing that habit

- Makes a behaviour satisfying: tracking is a reward in itself, as it is satisfying to see your results visually grow and accumulate over time

- It also motivates you to maintain your focus on the process of a habit rather than a desired result

- Also acts as visual proof of votes casted for the person you want to become

how do we make habit tracking easier?

- Automate measurement wherever possible (as you are already tracking things like steps, spending and places you have travelled to without knowing it, you just need to know where to get the data, and review it every week)

- Limit manual tracking to your most important habits (better to consistently track 1 habit than inconsistently track 10 habits)

- Record a habit immediately after you do a habit (where completing a beavhiour is the cue to write it down:

after **[CURRENT HABIT]**, I will **[TRACK MY HABIT]**

what do we do when a habit streak ends?

never miss twice

- Life is not perfect, and has interruptions. But, if you can’t be perfect, you can still avoid a second lapse

- Start a new streak as soon as one ends - it doesn’t matter if we break a streak if we reclaim it quickly and don’t give up

The first mistake is never the one that ruins you. It is the spiral of repeated mistakes that follows. Missing once is an accident. Missing twice is the start of a new habit.

- Showing up on ‘bad’ days is just as important as succeeding on ‘good’ days: just because you can’t do something perfectly doesn’t mean you shouldn’t do it at all

- Doing less than you hope might not make you better at the thing, but it still is a cast for your new identity as someone who does those things

how do we measure the ‘right’ thing?

Goodhart’s Law: “When a measure becomes a target, it ceases to be a good measure”

- Just because something is measurable doesn’t mean it’s important

- It is only useful to measure a habit quantitively if it is context as part of a larger picture of progress, and not the single thing that consumes you and how you define ‘success’

- Regardless of how you measure improvement (which a habit might be a part of), habit tracking makes habits more satisfying, and encourages you to ‘show up’

17. How an accountability partner can change everything

-

We avoid a behaviour if the ending is painful

- When the consequences of doing something are much greater, we learn faster to avoid the behaviour (assuming that the strength of the punishment ≥ strength of behaviour, and that it is reliably enforced)

- So, to break bad habits, add an instant cost and pain to doing the unhealthy behaviour

-

Habit contracts: a verbal or written agreement where you (a) state your commitment to a habit and (b) state the punishment for not following through

-

You find accountability partners to sign the contract with you to make sure that you follow up on the punishment for not doing the habit

e.g. punishment of paying a fine of $100 for not tracking your meals that day (makes failing to do the habit painful)

-

It seems a little unnecessary, but it is an indication that you are serious about establishing the habit

-

-

Accountability partners are useful, as knowing that someone is watching and judging you for doing / not doing a habit is a powerful motivator (your reputation is at stake)

- Hinges on the fact that we care about what those around us think of us

Laws of Behaviour Change: Summary PDF

Advanced Tactics

18. The truth about talent (when genes matter and when they don’t)

- The secret to making success likely is being in the right field of competition

-

If you choose the right habit, progress and sticking to the habit is easier

-

Habits are easier and more satisfying if they align with your natural abilities and inclinations

-

Our personalities nudge us in a certain direction, even if our habits are not entirely determined by them (as our preferences instinctively make some behaviours more attractive than others)

genes do not determine your destiny. They determine your areas of opportunity.

-

So, build habits that work for your personality

You don’t have to build the habits everyone tells you to build. Choose the habit that best suits you, not the one that is most popular.

There is a version of every habit that can bring you joy and satisfaction. Find it.

-

-

Genes give a powerful advantage when conditions are favourable, and a disadvantage when conditions are unfavourable ⇒ our environment determines the utility of our talents

- In practice, you tend to enjoy things that come more easily to you, as you more readily receive the indicators of success that motivate you to persist with that behaviour (because if you are successful in something, you are more likely to be satisfied)

- Choose habits that are easy for you (more success ⇒ more motivation to persist)

-

Direct your effort towards things that excite you and align with your natural skills

-

Explore/exploit trade-off: a way to find the right game for your skillset

-

When you start a new activity, begin with a period of exploration

- To try out as any possibilities as possible by casting a wide net

Questions to ask yourself to narrow down on the habits and areas that will be most satisfying for you

- “What feels like fun to me, but work to others?" (work that hurts you less than others)

- “What makes me lose track of time?" (and enter a flow state ⇒ a combination of happiness and peak performance ‘in the zone’)

- “Where do I get greater returns than the average person?" (behaviours tend to be more satisfying when we are better at them than other people)

- “What comes naturally to me?"

- Ignore what you have been taught by society and your internal judgements

- Ask yourself what makes you feel alive, as the real me?

- What do you enjoy most? What are you most engaged in?

- Whatever feels most authentic and genuine is the right direction

-

Then shift your focus to exploit the best solution you’ve found so far, but continue to occasionally experiment

-

If you are currently winning, continue to exploit that niche; if you are currently losing, continue to explore and look for new niches

-

In the long run, focus on the best strategy 80-90% of the time, and continue to explore with the remaining 10-20% of your time

- This is what Google does with their 80% work and 20% personal projects plan

-

-

If you can’t find a game that is angled towards your strengths, create one

- If you can’t win by being better, win by being different

- By combining skills, you reduce competition and make it easier to stand out

A good player works hard to win the game everyone else is playing. A great player creates a new game that favours their strengths and avoids their weaknesses.

-

-

Genes can’t make you successful by themselves: you have to do the work to realise your potential

Genes don’t eliminate the need for hard work, they tell us what to work hard on

-

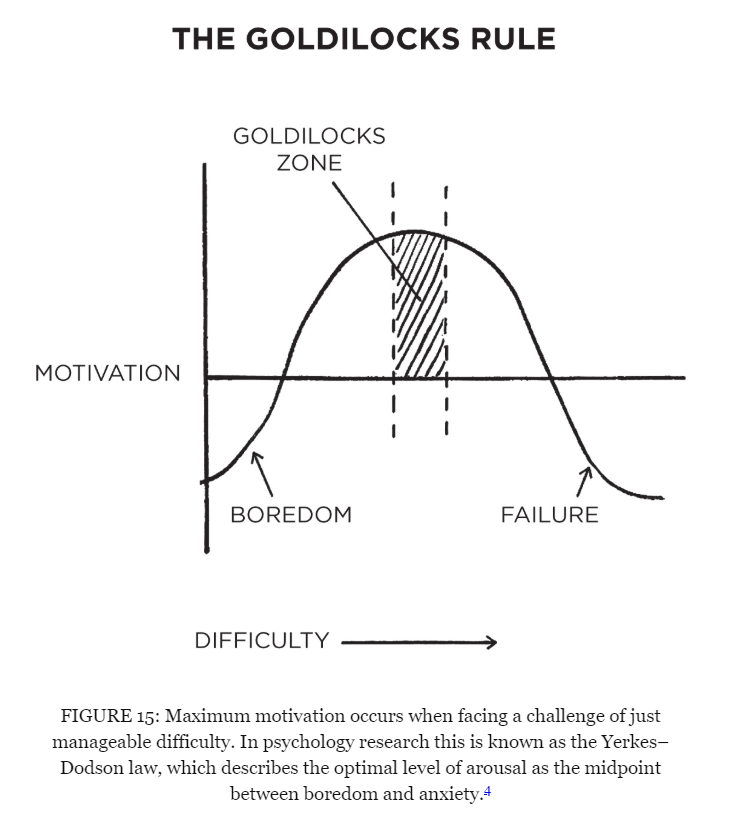

19. The goldilocks rule: how to stay motivated in life and in work

-

Goldilocks Rule: we have peak motivation when doing things that are at a manageable difficulty, on the edge of our current abilities (not too easy, and not too hard)

- When starting a habit, keep it as easy as possible to help you stick with it

- When a habit is established, advance and improve on it in small ways, staying in the Goldilocks Zone to keep you engaged (and achieve a flow state)

-

Successful people feel the lack of motivation that we all experience, but the difference is that they still show up despite feeling bored

-

With increases mastery, the more boring it seems, and the lower our interest (as the novelty of doing something decreases)

-

Boredom is the biggest threat to success (we get bored with habits if they don’t delight us, and the outcome becomes expected)

-

This is why, even if our current strategy is working, we look for a new strategy or productivity hack every time we have a dip in motivation

-

Working on challenges of just manageable difficulty is a way to maintain novelty

-

But, at some point “you have to fall in love with boredom”

-

You have to show up even if it is annoying, boring or draining to do so

Professionals stick to the schedule; amateurs let life get in the way

The only way to become excellent is to be endlessly fascinated by doing the same thing over and over. You have to fall in love with boredom.

-

20. The downside of creating good habits

- Habits are helpful: they help us perform the simple movements without thinking, freeing up our mind to focus on more advanced details

- Habits are dangerous: when you can do things ‘good enough’ on automatic, you might not think about how you can do things better, and might not pay attention to small errors

Habits are necessary, but not sufficient for mastery.

- You need to combine habits with deliberate practice (as some skills need to be automatic, but also a skill has to be continually improved)

- Mastery is about focussing on small elements of a skill, repeating them until they are habits, and then using this as a foundation to build new habits

- You have to be careful not to become complacent with mastering a single habit

-

Review and reflection is a way to continually adjust your habits and avoid complacency ⇒ to spend time on the right things and adjust our course where necessary

- It makes you aware of your mistakes and enables you to improve your habits in the long-term

- If we don’t do this, we can fall into the trap of making excuses for our poor performance

e.g. End-of-year Annual Review (reflecting on previous year)

- Tally habits for the year (e.g. how many articles published; workouts done; places visited)

- What went well this year?

- What didn’t go so well this year?

- What did I learn?

e.g. Summer Integrity Report (to realise where you are going wrong by revisiting core values and seeing if you are living in accordance to them)

- What are the core values that drive my life and work?

- How am I living and working with integrity right now?

- How can I set a higher standard in the future?

-

Brings a sense of perspective, to help us understand how our habits are fitting in to the wider picture of identity-change (done through periodic reflection and review) to see the important changes to make without losing sight of the wider picture

You want to view the entire mountain range, not obsess over each peak and valley.

Everything is impermanent. Life is constantly changing, so you need to periodically check in to see if your old habits and beliefs are still serving you

A lack of self-awareness is poison. Reflection and review is the antidote.

-

Identity can work against you by creating a ‘pride’ in certain values that may drive you to ignore or skim over weak spots and resist growth and change

-

We can avoid this by making sure that no single aspect of our identity or belief is an overwhelming portion of how we understand ourselves

When you cling too tightly to one identity, you become brittle. Lose that one thing and you lose yourself.

-

Mitigate loss of identity by defining yourself in a way where your identity is flexible to your current role and way you live (e.g. I’m an athlete → I’m the type of person who is mentally tough and loves a physical challenge)

When chosen effectively, an identity can be flexible rather than brittle.

-

-

So, habits can be beneficial, but we have to be careful to make sure that we aren’t locked into fixed, previous patterns of thinking and acting, to make sure that we are adapted to the changing contexts within which we live our lives

Conclusion: the secret to results that last

The holy grain of habit change is not a single 1 percent improvement, but a thousand of them. It’s a bunch of atomic habits stacking up, each one a fundamental unit of the overall system.

Success is not a goal to reach or a finish line to cross. It is a system to improve, an endless process to refine.

- To improve your habits, rotate through the Four Laws of Behaviour Change to find the next bottleneck and get 1% better

The key to getting results taht last is to never stop making improvements.